A “Tariffied” Market Gets a Powell Push

Since January 22, 2018, when President Trump imposed the first set of tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines, markets have been under a threatening cloud of uncertainty as to the magnitude the impact tariffs would have on the economy. The uncertainty has been exacerbated by rhetoric that suggests that exporting nations bear the cost of tariffs, which contrasts with the understanding among virtually all economists that tariffs are like taxes and are ultimately borne by end consumers. Within this expansive range of impacts, it is broadly accepted that tariffs are not good for the U.S. or its trading partners, at least in the short run. Moreover, given the amount of trade between the U.S. and its number one trading partner and second largest global economy, China, it is no wonder why tariff worries remain top of mind for investors.

Since January 22, 2018, when President Trump imposed the first set of tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines, markets have been under a threatening cloud of uncertainty as to the magnitude the impact tariffs would have on the economy. The uncertainty has been exacerbated by rhetoric that suggests that exporting nations bear the cost of tariffs, which contrasts with the understanding among virtually all economists that tariffs are like taxes and are ultimately borne by end consumers. Within this expansive range of impacts, it is broadly accepted that tariffs are not good for the U.S. or its trading partners, at least in the short run. Moreover, given the amount of trade between the U.S. and its number one trading partner and second largest global economy, China, it is no wonder why tariff worries remain top of mind for investors.

Since January 22, 2018, when President Trump imposed the first set of tariffs on imported solar panels and washing machines, markets have been under a threatening cloud of uncertainty as to the magnitude the impact tariffs would have on the economy. The uncertainty has been exacerbated by rhetoric that suggests that exporting nations bear the cost of tariffs, which contrasts with the understanding among virtually all economists that tariffs are like taxes and are ultimately borne by end consumers. Within this expansive range of impacts, it is broadly accepted that tariffs are not good for the U.S. or its trading partners, at least in the short run. Moreover, given the amount of trade between the U.S. and its number one trading partner and second largest global economy, China, it is no wonder why tariff worries remain top of mind for investors.

The good news/bad news tug-of-war nature of China trade deal talks has been the major driving force of volatility to the market over the last year and a half. Since imposing the first tariffs, the market, using the S&P 500 for reference, has increased a mere 1.5% (1% annualized), despite “mini booms and busts” over that time. Few would argue that this is a lot of “excitement” to endure for such a paltry return.

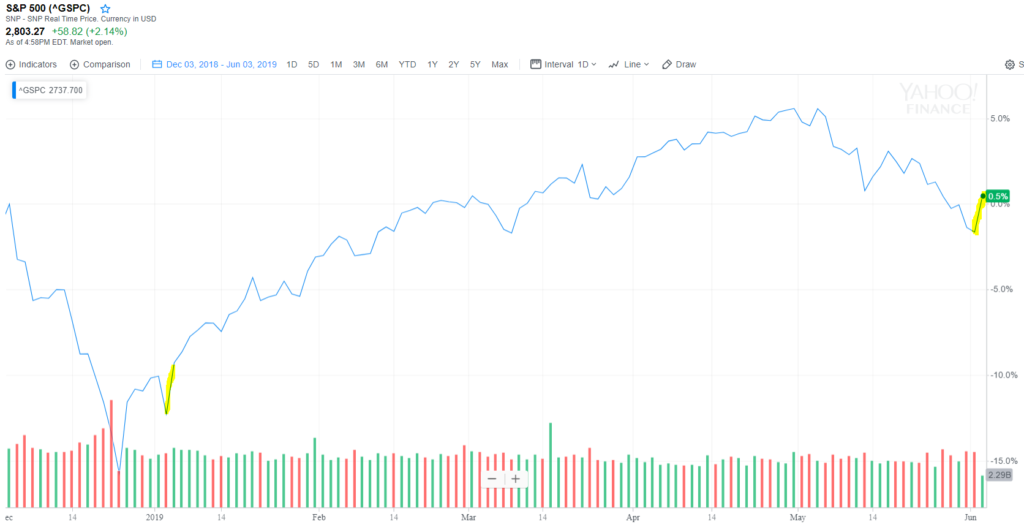

Adding to this strong thematic market factor is the Fed factor. That is, on January 4, 2019, following a sustained market decline in the 4th quarter of 2018, (chart from Finance.yahoo.com) Federal Reserve Chairman Powell announced that the Fed would “adjust policy quickly and flexibly,” marking an end to the Fed’s rate normalization policy (first yellow highlighted). The market embarked on a strong 4-month “relief” run.

However, on May 10, 2019, trade talks with China broke down suddenly and unexpectedly, which almost instantaneously sent the market sliding. The balance of May witnessed investors broadly moving away from equities in favor of the safety of bonds. Not surprisingly, Powell doubled-down on his dovishness on June 4th (second yellow highlight), by stating that the Fed would “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion,” a comment that all but confirms the expectation of a rate cut later this month and an increased likelihood of another before the end of the year (chart from Finance.yahoo.com).

While we might rightly gain comfort in Powell’s comment, it would be remiss not to peel back a layer or two of the onion. Consider that the Fed’s official mandate is to: 1) support full employment; and 2) maintain price stability (i.e. control deflation and inflation). By most economists’ standards, the Fed has achieved and continues to achieve its mandate. Few would argue that we are not at full employment with a historically low 3.6%1 unemployment rate and that price stability is not in check with a ~1.9%2 avg inflation rate over the last several years. But, peeling back a layer of the onion by contrasting Powell’s comment to this mandate reveals something. With the economy not having any real risk of inflation, he and the Fed are signaling that they see a risk of deflation, which typically accompanies a recession or at least a worrisome level of slowdown of growth in the economy. So, we should not mistake Powell’s comment as supportive of the market, but rather as insurance against a recession.

In this light, Powell’s comment accords with our recent and continuing expectation of an economy that fails to achieve sustaining growth momentum based on fundamental drivers of productivity growth and “animal spirits” stemming from positive long-term growth expectations, and a market that reflects that uncertainty through periodic bouts of alternating positive and negative periods bookended by sudden and unexpected turns.

In this market environment, we prefer balanced portfolios that have lower volatility profiles and which offer opportunities to add equity exposure on significant market sell-offs. Also, we believe passive index allocations to strategies that trade off upside potential in exchange for downside protection make sense for some portfolios. Moreover, as we shift to a more distinct bucket strategy for overall portfolios, we’re incorporating managed accounts with active stock picking for more dedicated equity exposures.

We will look forward to our next discussion to introduce these ideas with you. If you don’t hear from us over the next few months, please reach out to us to schedule an investment review meeting.

Sources

1. Bureau of Labor Statistics

2. usinflationcalculator.com

Both Charts are from finance.yahoo.com